- 8 February 2024

- 620 defa okundu.

Herzog & de Meuron’s Vision: The Lusail Museum Narrative

Qatar Museums reveals new architectural renderings of the future Lusail Museum, designed by Herzog & de Meuron.

Qatar Museums today released new renderings and a virtual flythrough video of the future Lusail Museum, revealing new details of the building for this world-class arts institution and global think tank designed by the Pritzker Prize-winning Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron.

With its unparalleled collection of Orientalist art, the Lusail Museum will explore the movement of people and ideas across the globe, past and present, helping to bridge a divided world through dialogue, art, and innovation.

With the participation of distinguished scholars, artists, policy makers, thought leaders, curators, and others, the Lusail Museum will provide opportunities for high-level study, discussion, debate, and mediation on critical global issues.

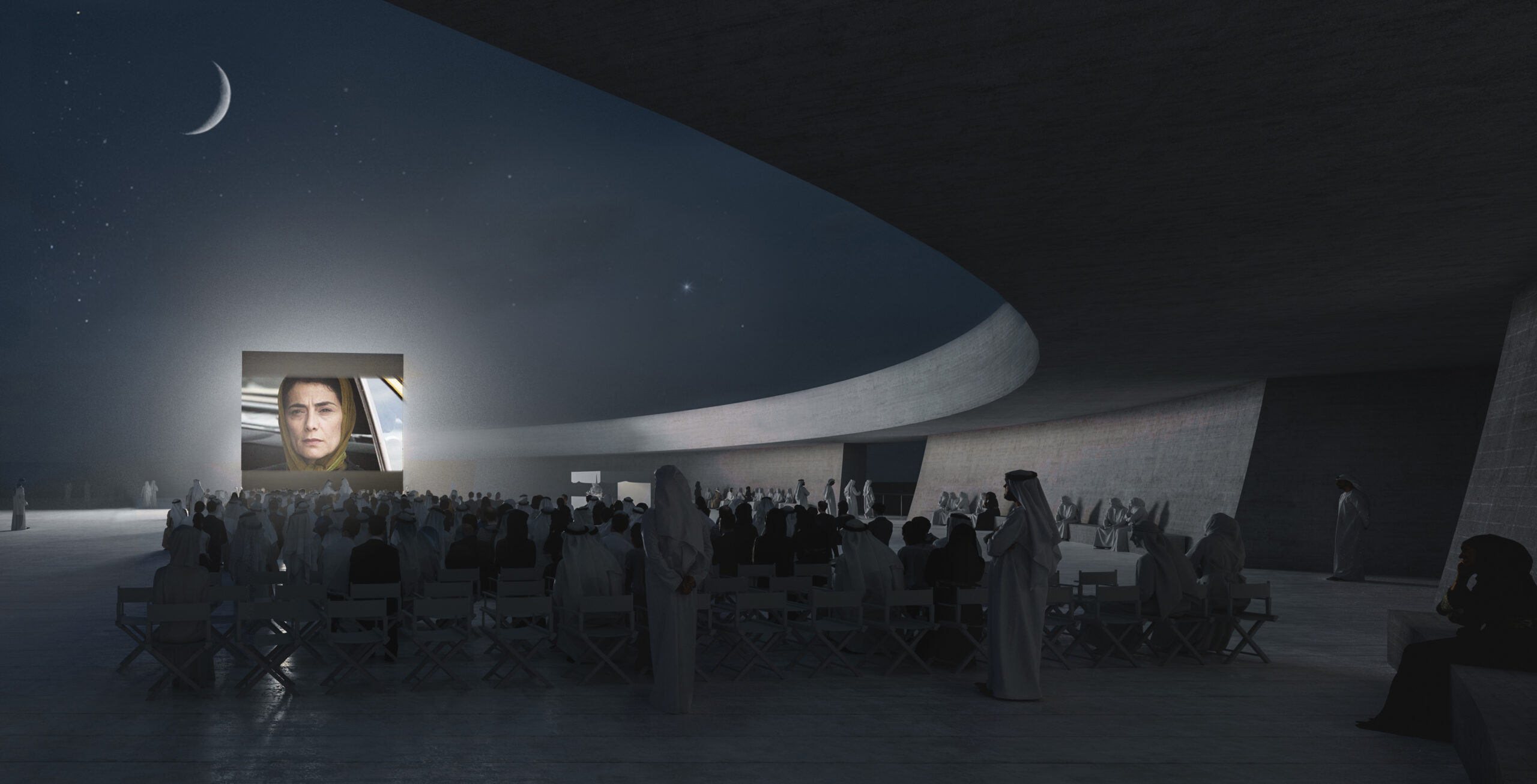

The design for the museum expresses this mission of convergence and conversation in a building conceived as “a vertically layered souk, or miniature city contained within a single building,” which will be the cultural anchor of Lusail City, the sustainable city now being realized north of Doha.

Qatar Museums’ Chairperson, Her Excellency Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, discusses the design with Jacques Herzog in the inaugural episode of “The Power of Culture,” her podcast exploring the modern cultural development of Qatar, which debuted in December 2023.

In the episode, Herzog shares his approach to architecture and the inspiration he drew for the Lusail Museum from local materials and the historical significance of the location, which is near the area where Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani, founder of modern Qatar, made his home in the late 1800s.

Herzog & de Meuron’s design for the museum occupies the southern tip of Al Maha island and acts as a physical marker within the island. The plan takes the form of a circle, which conveys both universal meaning and a specific response to the building traditions of the Middle East and Doha.

Three intersecting spheres shape and carve the volume of the building into two distinct parts: one resembling a full moon, the other a crescent moon wrapping around it.

Double curvatures derived from the spheres form a crescent-shaped internal street naturally lit from above; it serves to connect the entrances of the museum to the central lobby and other public functions such as a library, auditorium, shop, café, and prayer space.

The building exterior is rough, earthen, sand-like and resilient, in response to its coastal setting; it appears as if it is a piece of the land itself. Daylight enters the interior spaces through deeply recessed windows cut out of the façade, protecting the interiors from direct sunlight; the surrounding sea and city of Lusail remain constantly visible.

Collaborations with local and regional artisans and craftspeople will ensure a direct connection back to the local vernacular and reinforce the project’s role in preserving historic trades and fostering cultural exchange.

Within the robust concrete expression of the building, spaces inserted as counterpoints bring a different scale, material quality, and sensory experiences for the visitor.

A central sculptural polished plaster stair, a reflective metal prayer space, a wooden-paneled library, a soft and intimate auditorium, and several cushioned and upholstered niches throughout all feature a variety of haptic qualities and materials such as wood, textiles, metals, and ceramic tiles.

The display spaces on the gallery floors differ in shape and proportion depending on their location, yet all provide flexibility for various types of exhibitions.

Four abstract replicas from the interior of important historical buildings are inserted into the top gallery floor as anchor spaces: The dome covering Murat III’s bedroom pavilion in the Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul (1579); the dome of the Jameh Mosque in Natanz (1320); the Ablution fountain in the courtyard of Ibn Tulun Mosque in Cairo (1296) and the Aljafaria dome in Saragossa (1050); four cupolas with distinct geometry and ornamentation relating to their geographical heritage.

Pendentives, cross arches, muqarnas and squinches are the defining geometries of the selected dome typologies.

They are used to break the sequence of the more traditional galleries and to provide exceptional curatorial and educational opportunities while offering unexpected spatial experiences.

The dome has been chosen as the architectural typology for these four rooms, each of which is universal and specific at the same time; universal because domes have appeared across cultures throughout time, and specific because the singular “ideal” form of the dome has developed variations through local geographic and cultural influences.