- 10 September 2024

- 163 defa okundu.

House 8

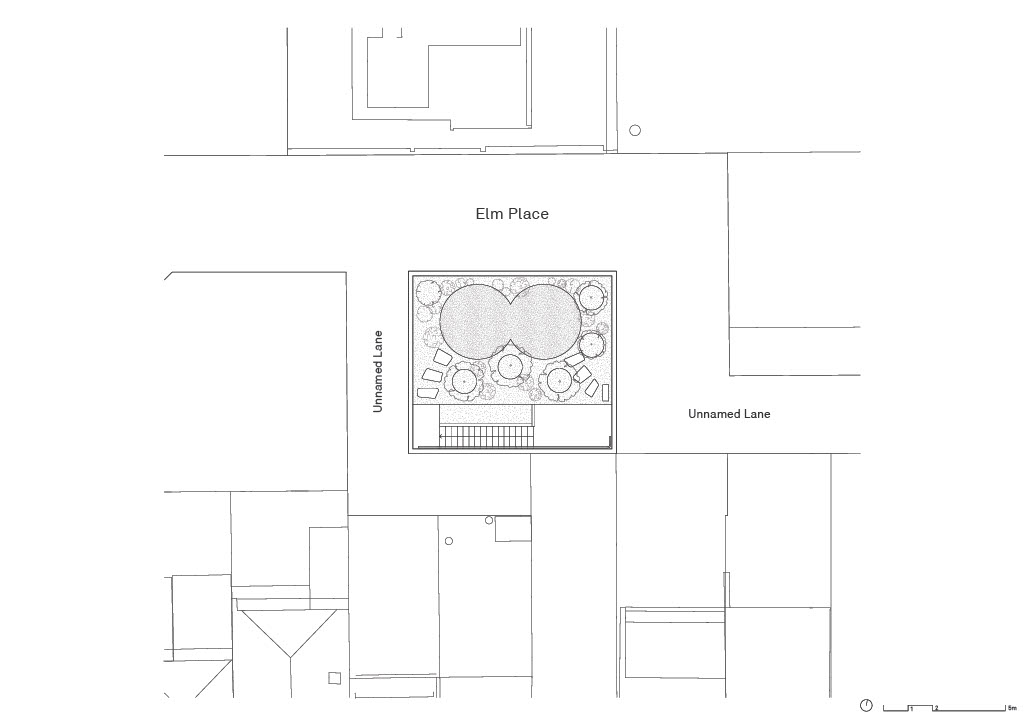

House 8, designed by Common ADR in North Melbourne, Australia, is a living experience that transforms a neglected street space into a sustainable single-family residence inspired by the surrounding heritage urban fabric.

The House for 100 Years is a misnomer.

This project should perhaps be titled House, Factory, Nightclub, Office and Anything else for 100+ years, but that’s too much for mouthful.

The average lifespan of buildings in developed economies have collapsed by 75% between 1900 and 2001.

As Koolhaas noted; the most important, and least recognized, difference between traditional and contemporary architecture is that the moral and aesthetic concerns motivating pre-modern architecture resulted in robust adaptable buildings; while the deterministic co-incidence between form and program in modern architecture has proved highly inflexible.

The House for 100 Years investigates how we can increase the longevity of buildings by thinking about their use across their entire lifecycle and how buildings respond to the tangible and intangible heritage encoded in built environments around them.

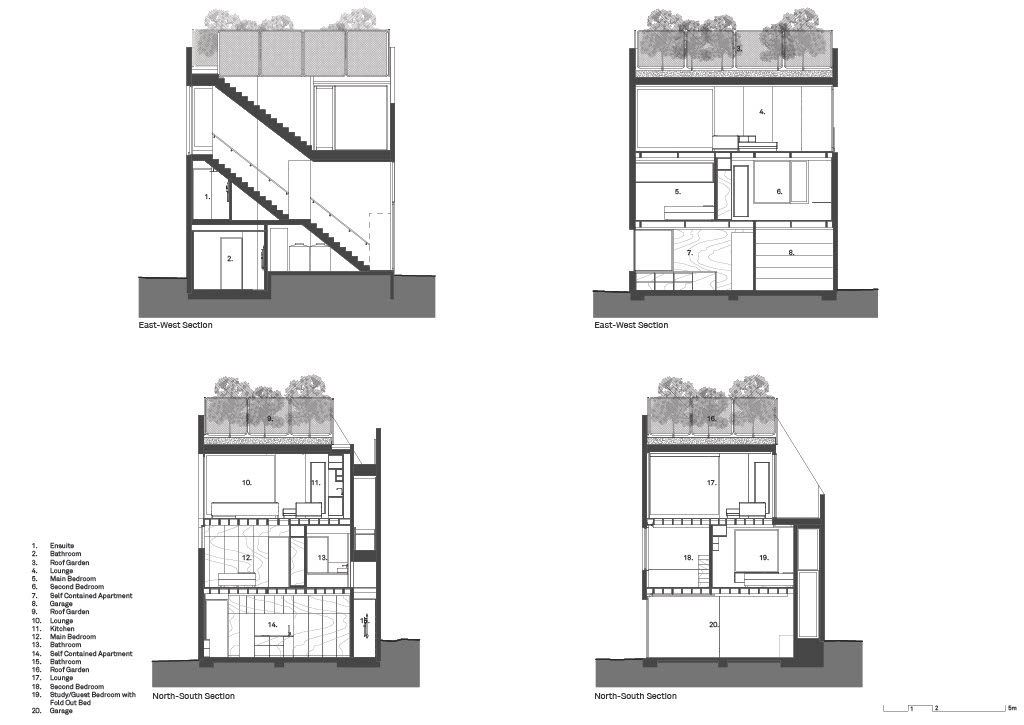

The small 8x8m site, precluded the use of scaffolding, leading to the selection of pre-cast concrete as the principal structure.

This skin is articulated with a continuously differentiated surface pattern that reinterprets how facades of historic buildings around the site have increased surface articulation in areas around windows and doors drawing that draw visual attention and deflecting water and dirt away from these openings.

A digital script was developed to reinterpret this historic contextual trait, producing fields of increased surface articulation near windows and doors.

This topologically complex surface was then milled and used as moulds for the precast concrete wall panels.

The completed concrete skin reference and transforming a brutalist tradition of articulated concrete through a contextual response that utilises digital design tools and fabrication.

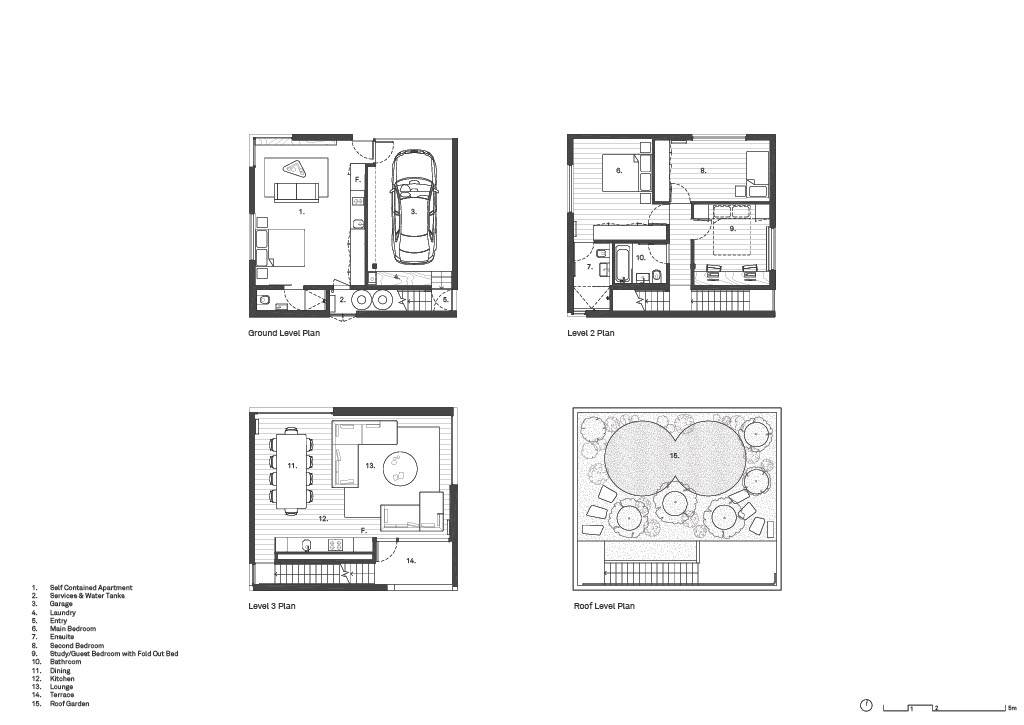

Drawing inspiration from the versatile warehouse typology prevalent in the area, the design prioritizes adaptability, with column-free interiors and strategically positioned services, the building can seamlessly accommodate various functions, from residential to commercial, over its lifetime.

The exterior concrete shell of the building is structurally independent, producing an 8x8x8m high enclosed volume.

That is infilled with timber floor framing which allows for easy reticulation of services and almost any internal reconfiguration of the building to occur without structural recertification.

This use of local hardwood timber facilitates both adaptation within this building but also eventual disassembly and reuse on other sites in future.

This robust and adaptable approach maximises the life of the building and ensures that the embodied environmental impact of the project is mitigated over the maximum amount of time, rather than being lost when the project no longer fits the purpose it was originally designed for.

In a disciplinary context where demolition is increasingly and justifiably unethical, The House for 100 Years attempts to answer the question of how to design buildings that won’t need to be demolished in two ways; by deploying a set of strategies to elongate utility by facilitating flexibility and enabling future adaptive reuse and perhaps more importantly for architecture as a cultural discipline; by embedding cultural value in the fabric of the building through engaging and actively contributing to a place’s built heritage as a continuing, collective and common project.