- 28 March 2024

- 1212 defa okundu.

Seddülbahir Fortress

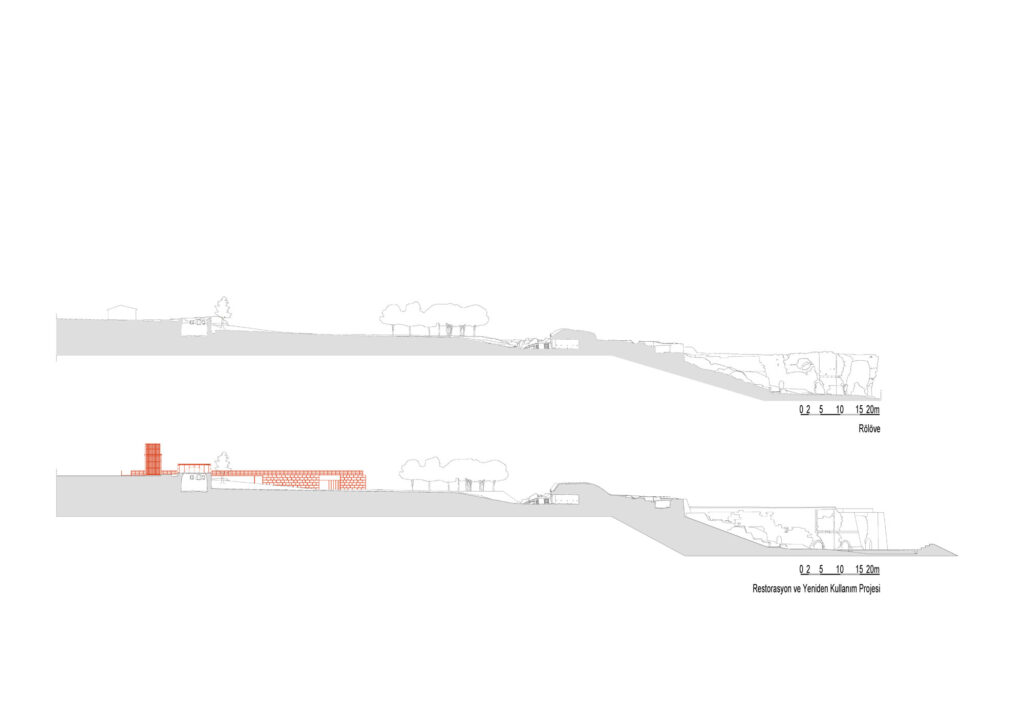

Seddülbahir Castle, whose survey, restitution and restoration projects were prepared by Arzu Özsavaşçı (AOMTD) and adaptive reuse project by Y. Burak Dolu (KOOP Architecture), and implemented under the supervision of Gülsün Tanyeli, Lucienne Thys-Şenocak, Rahmi Nurhan Çelik and Haluk Sesigür, is located in Çanakkale.

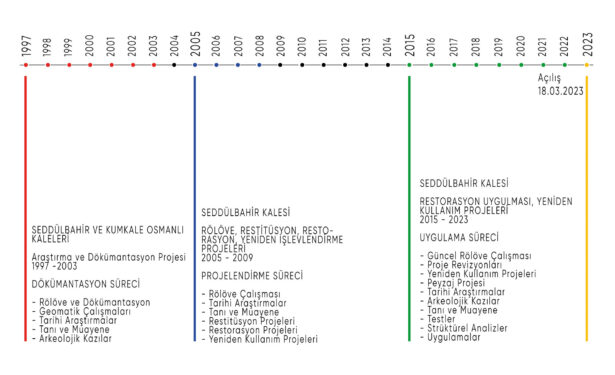

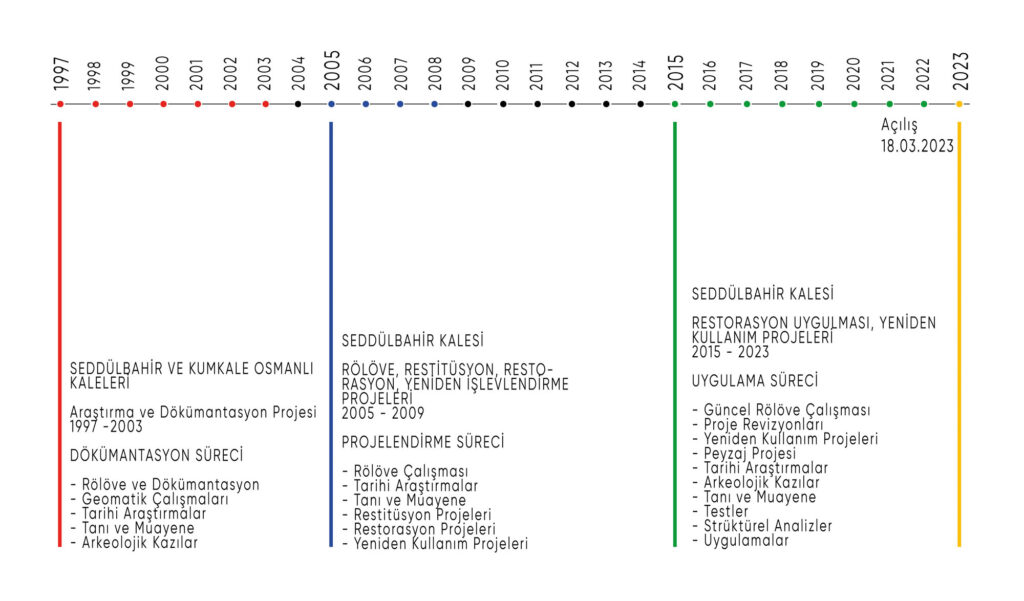

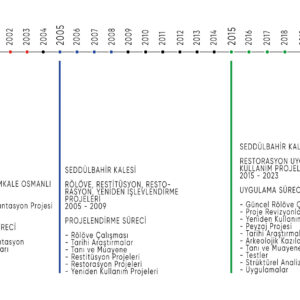

After 25 years of many intensive phases of project preparation and application, Seddülbahir Fortress was opened to visitors after the completion of the restoration work on March 18, 2023. The comprehensive academic research and documentation which was initiated in 1997 with the collaboration of Koç University and Istanbul Technical University in Seddülbahir Fortress, evolved into a detailed documentation project to support the conservation-restoration-reusage projects between 2005 and 2009. The projects were approved by the Çanakkale Regional Council for the Conservation of Cultural Properties at the end of 2009. The restoration and museum reusage applications, which were tendered by ÇATAB (Çanakkale Wars and Gallipoli Historical Area Directorate) in 2015 were completed in 2023.

The initial construction of the Seddülbahir fortress, or the “Wall of the Sea”, began in 1656 as a result of the patronage of Sultan Mehmet IV.’s mother, Hatice Turhan Sultan. Hatice Turhan Sultan is a rare example in Ottoman history of the patronage of military architecture by a royal Ottoman woman. According to different archival records the fortress was first built by a team working under the direction of the Ottoman court architect Mustafa Ağa. The fortress suffered great damage during the Battles of Çanakkale during World War I.

Seddülbahir Fortress was the first project selected by the Site Directorate ÇATAB on the Gallipoli peninsula, and the tender for its restoration was completed in 2015; shortly thereafter the restoration application process began. During the implementation process, the project team and consultants who worked in the field between 1997 and 2009 joined the team to form the Scientific Advisory Board and to ensure continuity. All the application details were discussed in more than 100 meetings in which members of the Scientific Advisory Board, the control organization, and experts from different disciplines participated. The fundamental approach to the fortress was to preserve as many of the elements of the structure as possible; interventions were made only when there was a structural necessity, a need for visitor safety, or situations that disrupted the architectural integrity of the fortress.

Since the start of the implementation phase in 2015, all aspects of the process have been presented in several publications, conferences, and other types of communications; information about the application process was also shared regularly with experts and members of the local community. The team expanded from 1997 to 2023 and included the devoted efforts of hundreds of people who continued to work with the excitement and enthusiasm that characterized the very first season of field work. Improvements continue to be made in all facets of the architectural project according to the feedback received from visitors after the opening. Work on the fortress in on going and includes the creation of creative scenarios for the use of the fortress, the production of academic publications, and other types of documentation projects.

Collective Process and Unique Conservation Approaches

Following the withdrawal of military forces from Seddülbahir Fortress in 1997, Prof. Dr. Lucienne Thys-Şenocak from Koç University, Department of Archaeology and the History of Art and Prof. Dr. Rahmi Nurhan Çelik from ITU Geomatics Engineering Department started a joint research project, initially at Seddülbahir Fortress and then at Kumkale. The interdisciplinary research team, together with many academic experts, undergraduate, and graduate students from these universities carried out historical and architectural research. With the ITU Geomatics Engineering Department a general survey was undertaken during this phase of project at both the Seddülbahir and Kumkale Fortresses from 1997 to 2004.

The project for the restoration of the Seddülbahir Fortress restoration officially started with the protocol signed between the Ministry of Forestry and the Vehbi Koç Foundation in 2005; this phase of the project was completed with the approval of the Çanakkale Council for the Conservation of Cultural Properties at the end of 2009. The preparation of the restoration project that was carried out during the period of collaboration between Koç University and Istanbul Technical University, included a comprehensive field survey using 3D laser scanning technology that was very new at that time in Türkiye. The data from the survey was then processed in the project office at the ITU Geomatics Engineering Department Lab.

During this phase of the project, art and architectural history research continued and archaeological excavations at Seddülbahir were carried out jointly with the Çanakkale Archaeology Museum. Material analyses and oral history studies were carried out as well. Restitution and restoration projects were completed based on the research and the results of the field work. The results of the project, which included, at that time, the first major 3D laser scanning and documentation of a historical structure in Türkiye, were presented in several international symposiums as well as other academic platforms. The diverse research became the subject of many MA and PhD theses, academic articles, book chapters, and university lessons.

The Gallipoli Peninsula had the status of a National Park between 1973-2014 and was under the responsibility of the General Directorate of National Parks of the Ministry of Forestry. With the establishment of the Çanakkale Wars Gallipoli Historical Area Directorate (ÇATAB) in 2014, the peninsula was given the status of a “Historical Area”. During this period of administrative changes, the research team working at Seddülbahir Fortress continued to communicate with different government institutions to ensure that the labor and efforts of the team would be taken into account and provide continuity in any future conservation, restoration and reusage projects.

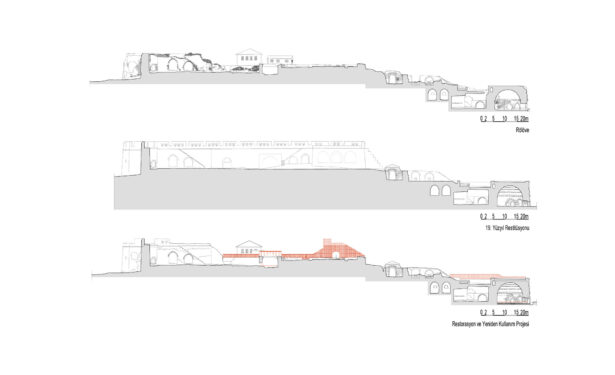

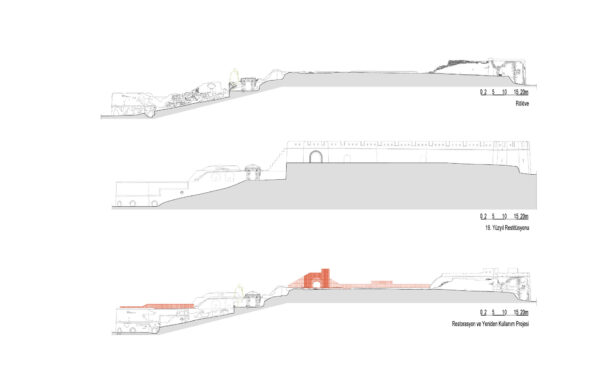

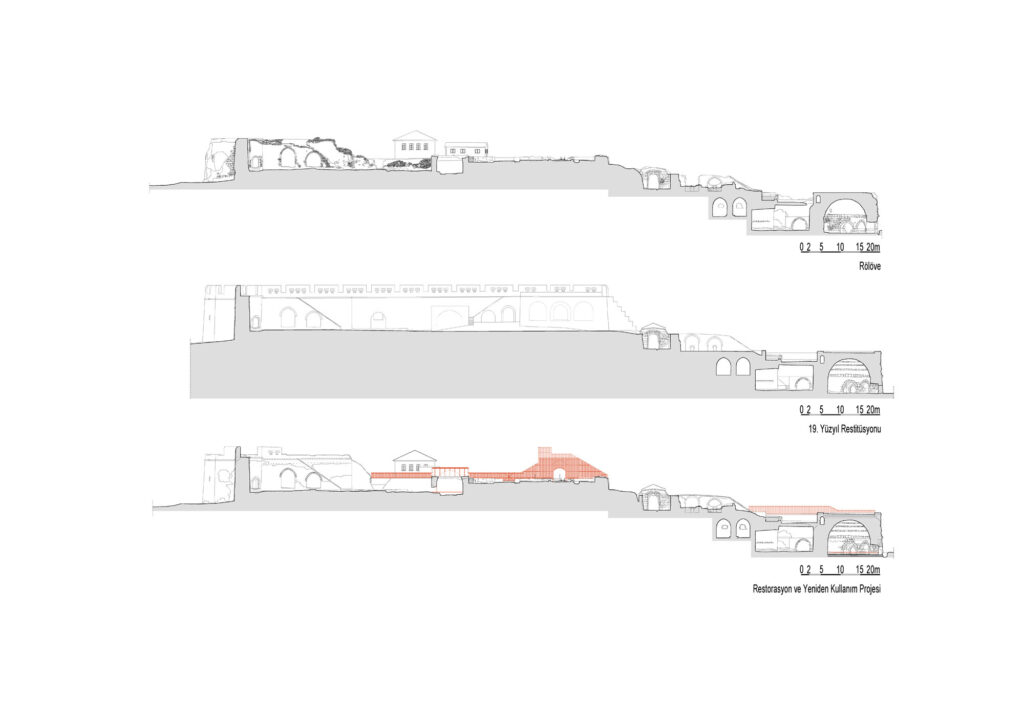

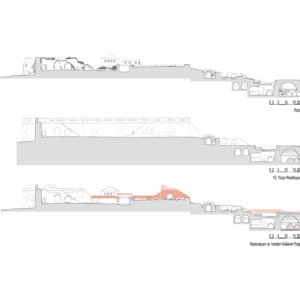

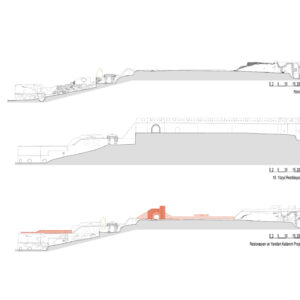

For the conservation and restoration of Seddülbahir fortress, several different decisions have been made about how to document, preserve, restore and/or reconstruct different parts of the structure and site. The need to preserve evidence of past destruction that occurred during the Çanakkale Wars (i.e. the West and South towers) was recognized as a crucial aspect of the interpretation of the site as these two towers, preserved as ruins, help to commemorate the battles fought at Seddülbahir and serve as evidence of the destruction that occurred during these wars. The decision to conduct limited reconstruction in some parts of the fortress (i.e. West wall crenellations) and to advocate again any reconstruction (i.e. the late 19th century Ottoman military barracks) were also decisions informed by recent debates in critical heritage studies concerning authenticity, theories about architecture and memory, the commemoration of the built heritage of war, as well as other interpretive needs. Since the beginning of the project in 1997, and during the restoration phase that began in 2015 the progress of the project has been shared openly and regularly with members of the local community at Seddülbahir along with other stakeholders, through publications, site visits and other activities.

Criteria for the Application and Implementation Process

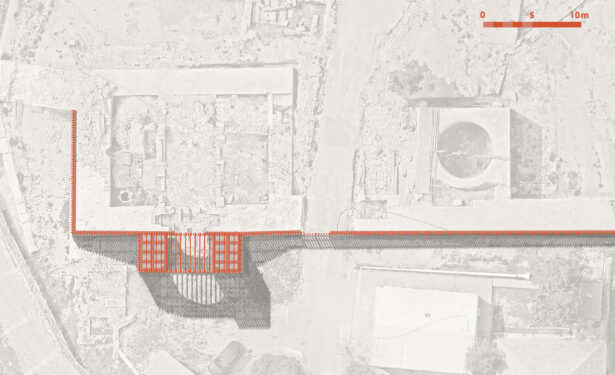

With the start of the restoration application in June 2015, cleaning the site was a priority at the Seddülbahir Fortress as it had been covered by vegetation for many years. The reinforced concrete structures and walls from the 1960s that had been built for military purposes were removed at this stage. As a result of comprehensive archaeological excavations, ruins from different periods of the fortress were discovered or further articulated. The late 19th century barracks in the upper fortress, the Bab-ı Kebir (Main Gate), the Southwest Tower, which was known to exist from archival records, but was buried and not visible, the foundations of the Southwest wall, and several other remains of structures within the fortress were discovered. With the building remains and substructures excavated, the original plan of the fortress has now become more understandable and more data has been obtained about the changes the fortress has experienced from the 17th through the 21st centuries. As a result of archaeological research and excavations, more than forty thousand archaeological finds were unearthed and important information regarding the late Ottoman period and World War One archaeology was collected.

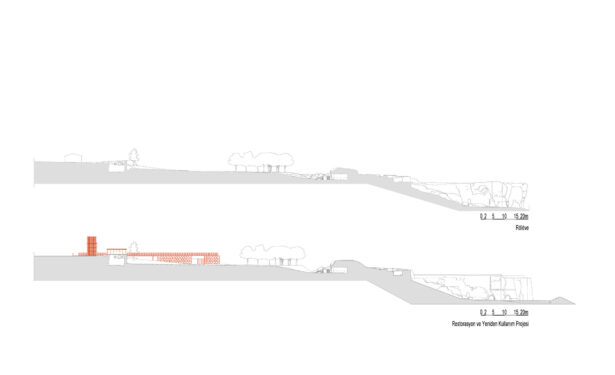

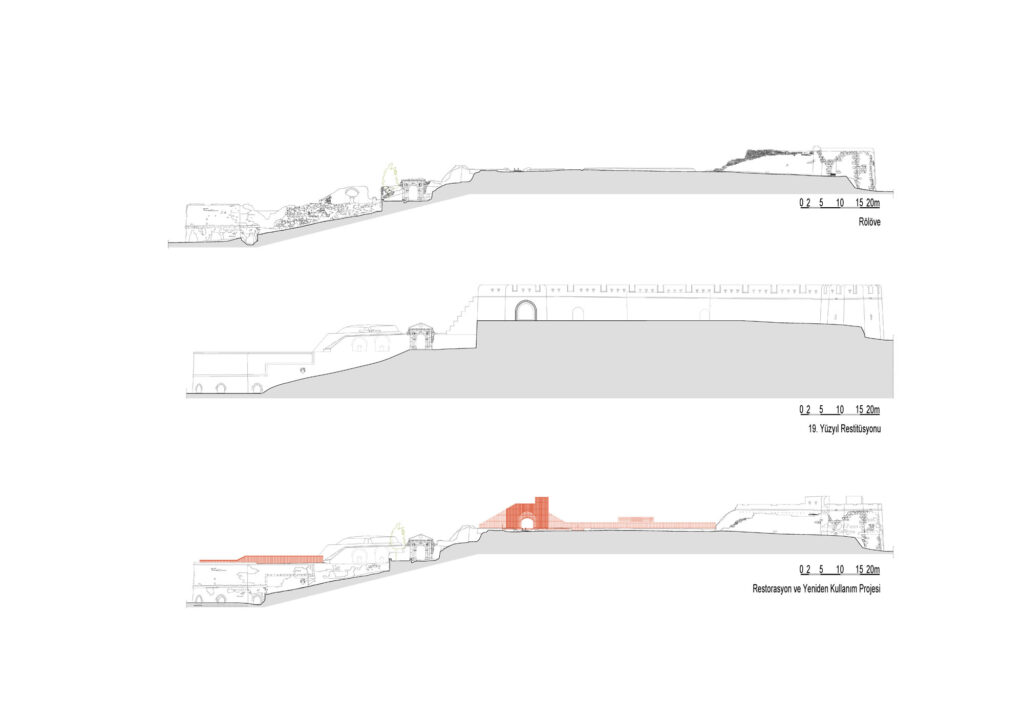

Updating the survey drawings that had been prepared between 2004 and 2009 was the priority of the work carried out during the later implementation phases of the project. New survey works were conducted and prepared which incorporated the information about the structures that had been discovered during the archaeological excavations, and application decisions were updated accordingly. Adhering to project decisions approved by the Çanakkale Regional Council for the Conservation of Cultural Properties, different eras of the history of the fortress were articulated in the restitution drawings. Also, with the help of one of the oldest archival records for the fortress, a detailed drawing of Seddülbahir signed by the French cartographer Berquin in 1700, the restitution project was able to present a more accurate scenario of the earliest phase of the fortress and its environs. Detailed studies of the restoration projects were updated and examined by the members of the Directorate control team, the scientific advisory board, and the technical staff working at the site. The survey work and all projects were submitted to the Council and the implementation of these decisions then started. At the completion of the restoration work, the as-built project of the site was prepared concurrently.

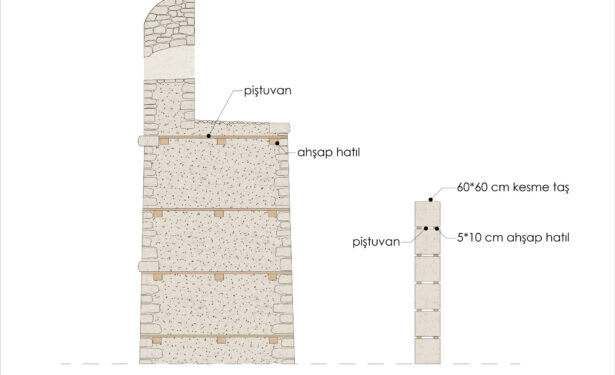

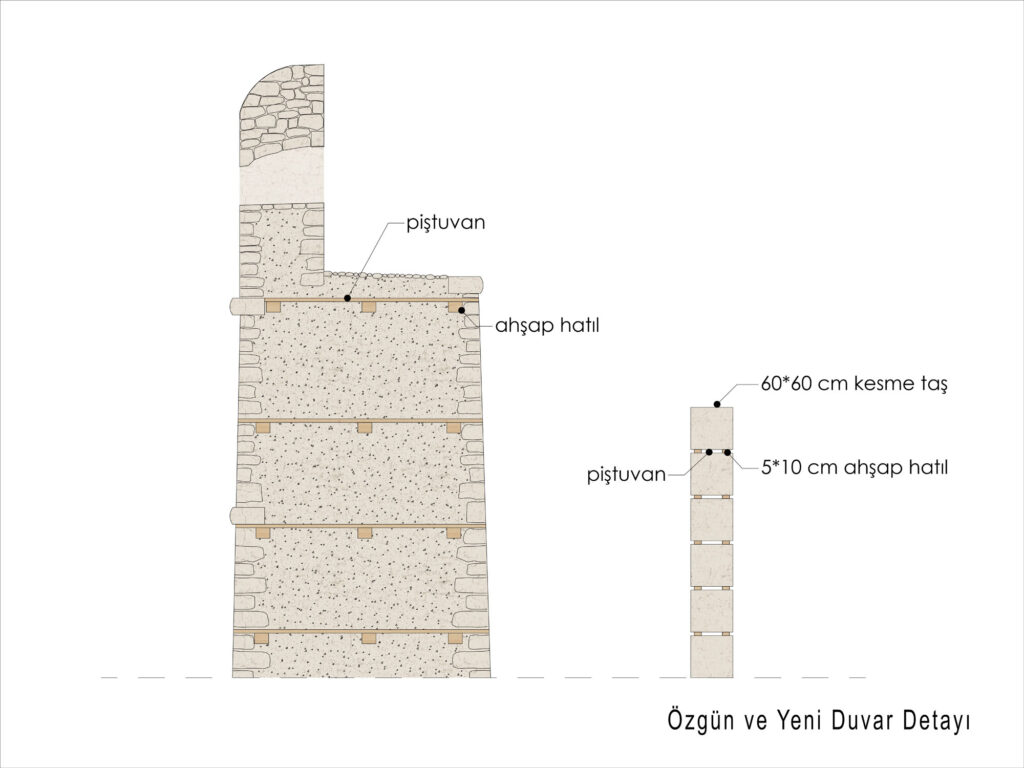

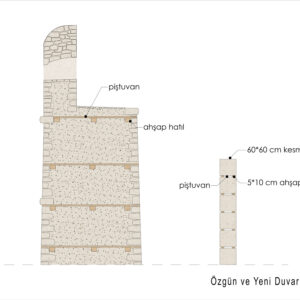

During the restoration, new information and new data on construction techniques and different building periods of the fortress emerged. One of the important discoveries was made about the Northwest Wall. After cleaning the soil and rubble on the upper level of that wall, traces of the crenellations from the first period of the building in the 17th century were found embedded in the later 19th century wall, the height of which had been raised and another set of crenellations added. This is evident in the photographs taken of this section of the fortress before the destruction of World War One. After detailed on-site findings and analyses of archival documents, dendrochronology research was also undertaken of this section of the wall. Then proposals for, intervention were made which presented both periods of crenellations. The foundations of the earlier crenellations were preserved, and some sections partially completed to indicate the original dimensions of these. A partial reconstruction of a few of the later crenellations was undertaken only to show the relationship between the two distinct periods of the long Northwest wall. All this helped to demonstrate a fundamental principle in restoration: how important it is to carefully research, preserve, and to present all the different eras of building’s past. A large gap in the same wall that had been partially opened during the war and then further dismantled for the construction needs of the village in the early 20th century was reconstructed to insure the physical and aesthetic integrity of that section of the fortress.

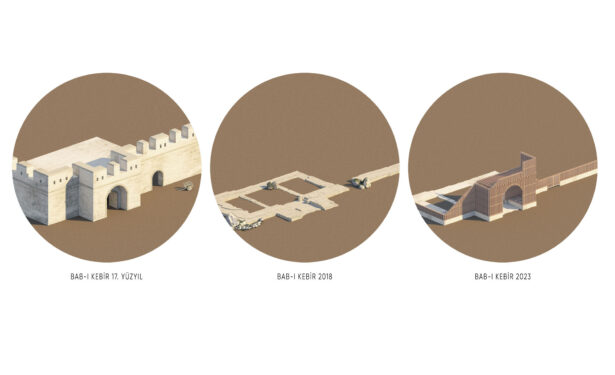

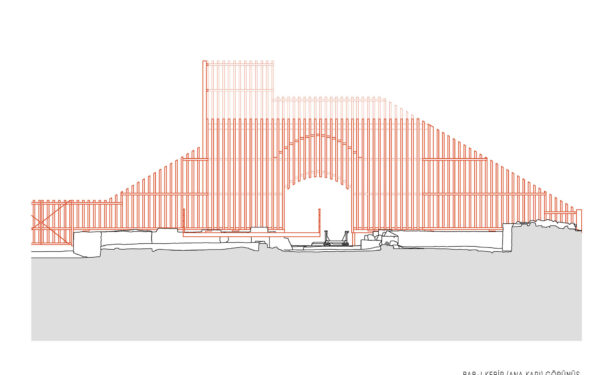

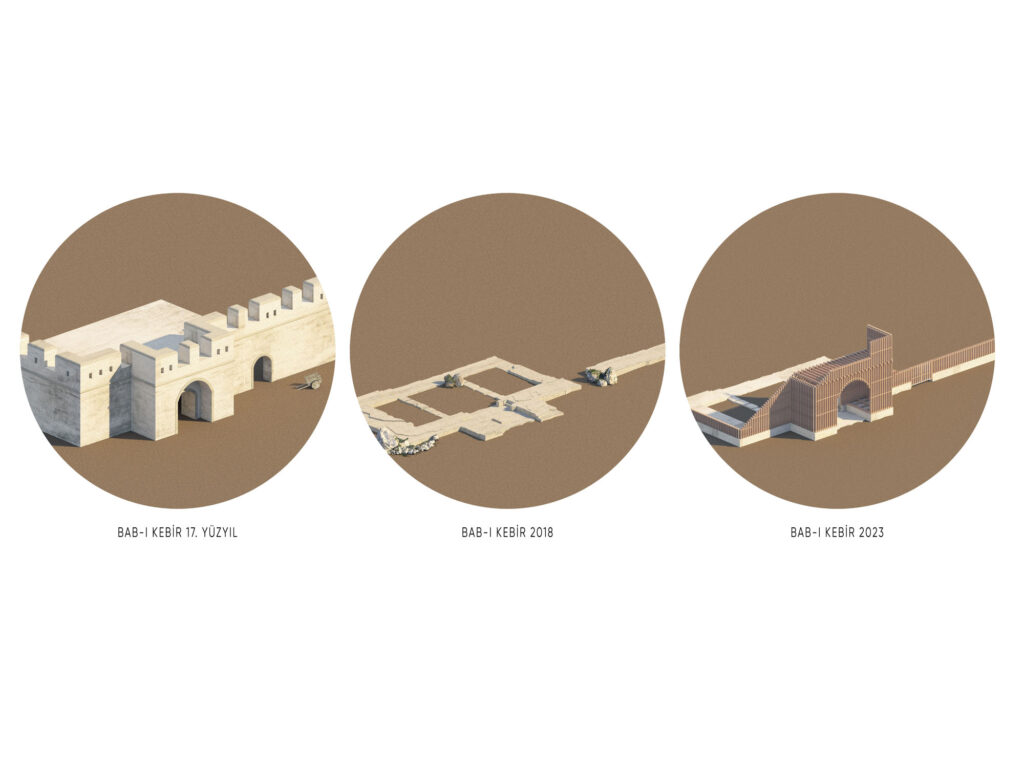

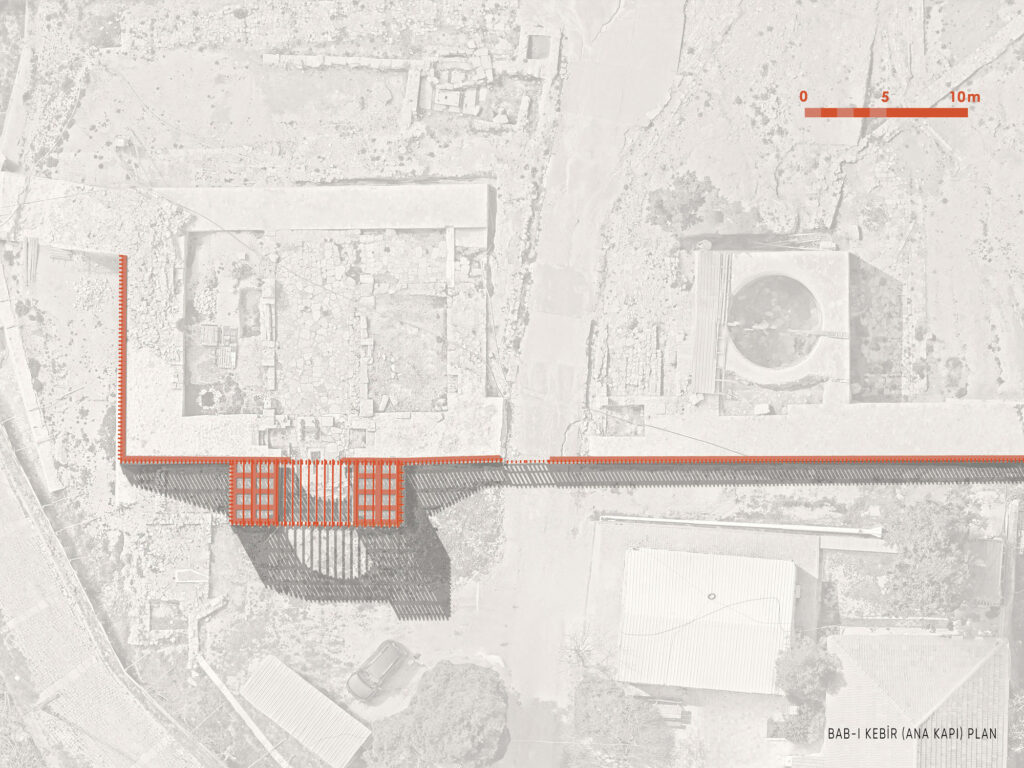

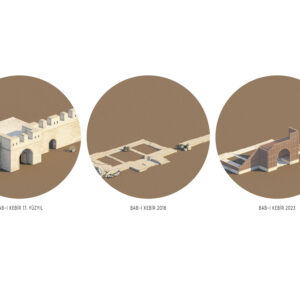

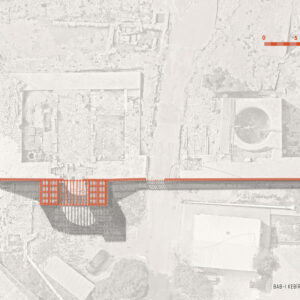

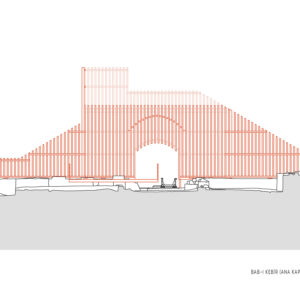

During the archaeological excavations carried out at the entrance of the fortress, the architectural remains of the Bab-ı Kebir, (Main Gate), which was heavily damaged during World War I and did not survive to the present day, were discovered. It was decided to preserve the ruins of the Bab-ı Kebir, to articulate the entrance axis to this structure and to design a modern addition to mark its original place. On the southwest slope of the fortress, the architectural remains of the Southwest Tower, whose existence was known from engravings and other archival records, but which was buried under rubble before World War One, was unearthed during the removal of rubble and archaeological excavations. Conservation decisions were also made about the foundations of the main late 19th century Barracks in the upper fortress and the Southwest Wall, and different sections of various walls were strengthened and preserved in their current state.

The West and South towers of the fortress had been heavily damaged in the Çanakkale Wars and were stabilized before the restoration because they posed a danger of collapsing. The restoration application was completed by making structural improvements and the remains of the domes of each of these towers were supported with buttressing so as to prevent further damage to the original building fabric. The decision not to reconstruct the West and South Towers of the fortress was an intentional desire to preserve the memory of destruction that the fortress of Seddülbahir experienced during the violent attacks to the fortress perpetrated by the Allied Forces during the Çanakkale Wars.

The aforementioned drawing by Berquin from 1700 also shaped the restoration process as it showed the location of the original coastline from the late 17th and early 18th centuries which has now receded to a dramatic extent. The drawing also revealed many of the structures within the fortress and adjacent village at that time. The jetty that was constructed during the restoration process followed the evidence from in the Berquin drawing and was reconstructed so as to save the lower South tower and its abutting walls from continued erosion and other damaging weather events. An underwater archaeological survey was conducted along the shoreline where the jetty was constructed and all evidence of earlier jetties of the shore was recorded. Several cannon balls were also excavated during this underwater archaeological survey and became part of the archaeological collection at Seddülbahir.

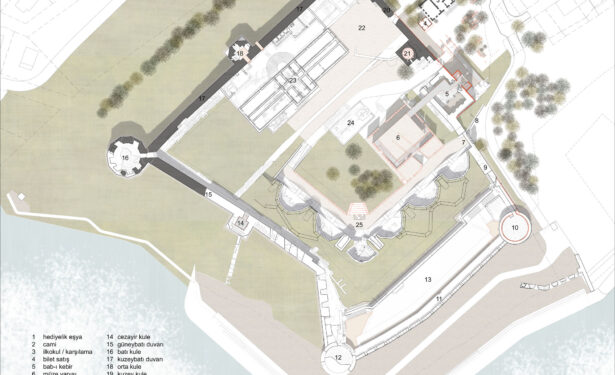

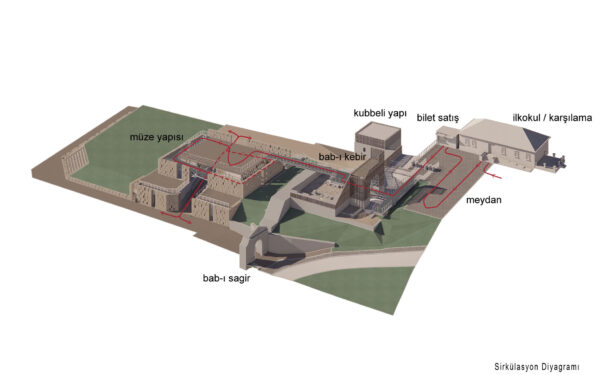

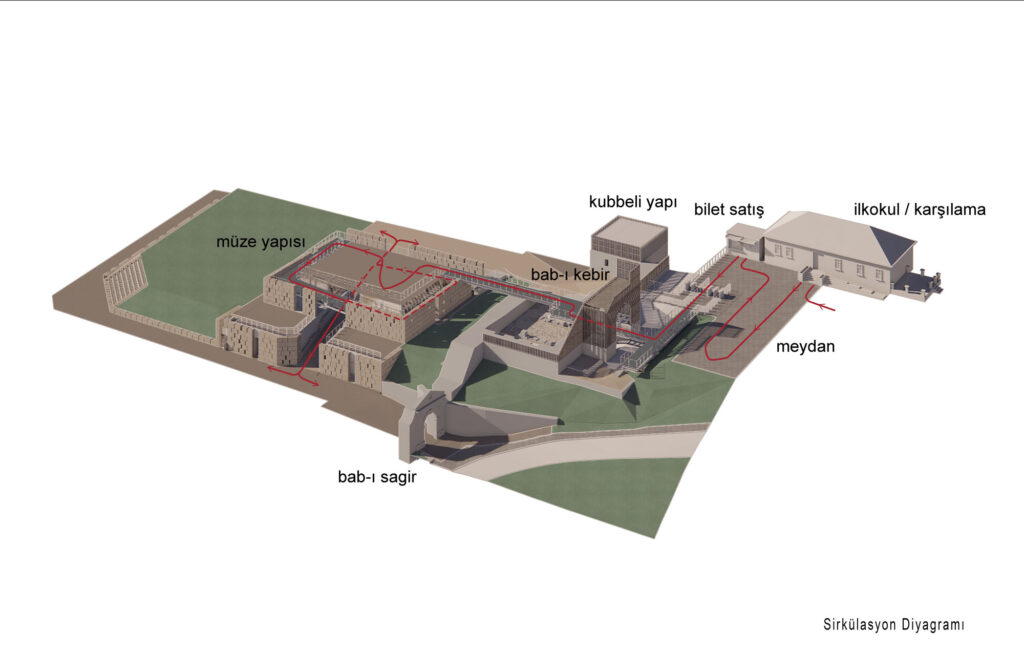

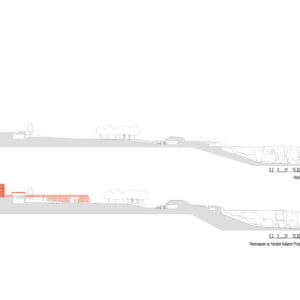

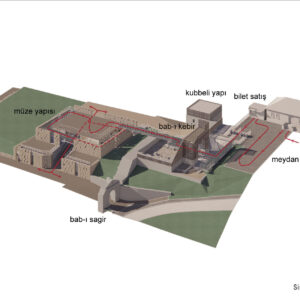

The Re-use project is one of the most important aspects of the project, and the team to undertake this task was selected as a result of an invited competition in 2017. Among the intentions for reusage was the creation of an entrance to the fortress which recalled in some way the destroyed Main Gate, and the creation of a new museum building within the fortress. In addition to these goals, the square in front of the fortress was redesigned, the primary school in the square was renovated and converted into a visitors’ center and center for local crafts production. New functions were given to many of the spaces within the fortress, and landscaping was undertaken for the entire site and its environs. Planning for visitors with disabilities was also undertaken at this time and walking paths and accessible spaces and routes through the sites were created.

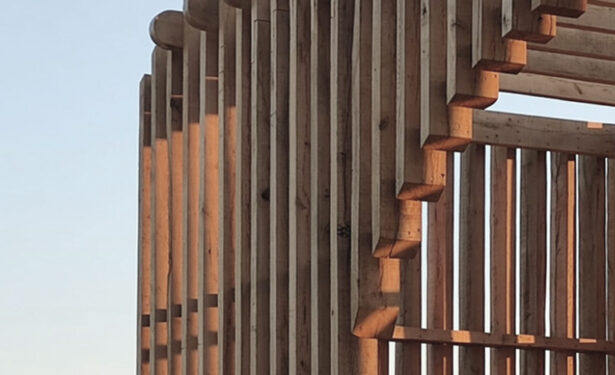

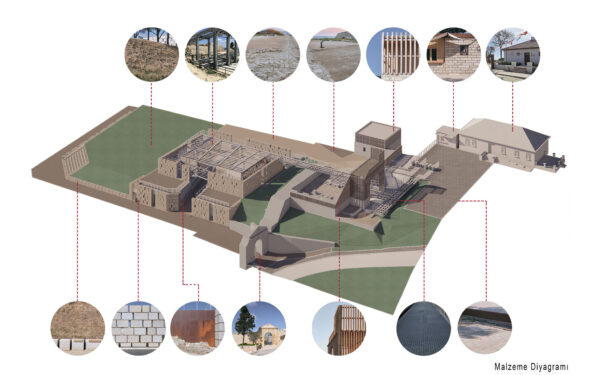

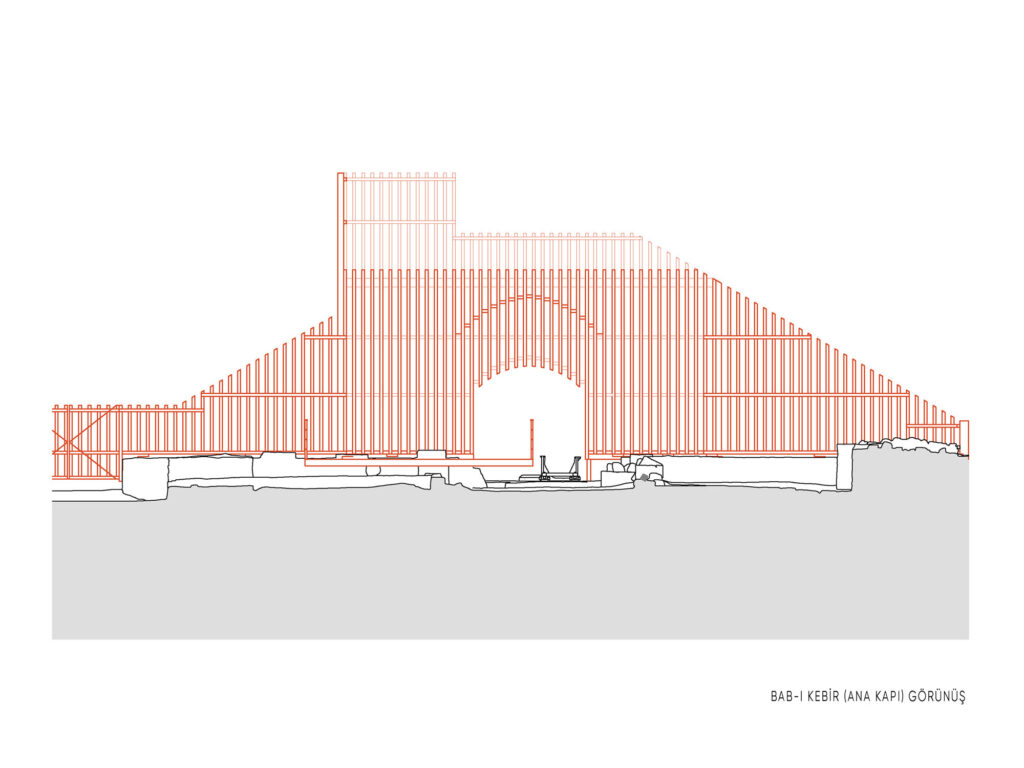

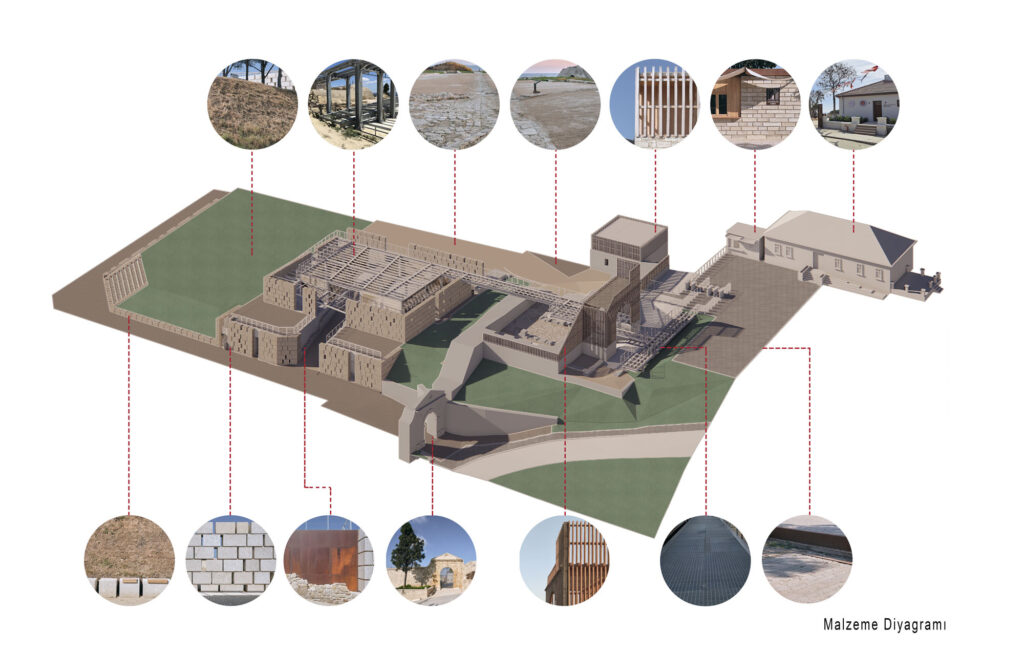

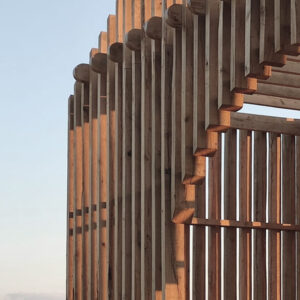

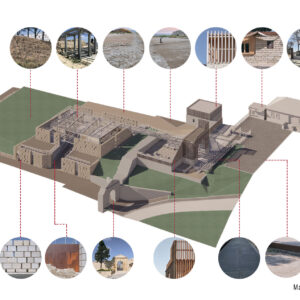

Instead of a heavy-handed restoration approach to the entrance of the fortress which would use more permanent types of materials such as stone or brick, a proposal for the Main Gate was made which suggests an outline of what these sections of the fortress, particularly the Main Gate and the Domed Building at the entrance, may have looked like originally. If a reconstruction of these elements had been done many of the existing remains in the entrance area would have been destroyed or become largely invisible under a new layer of construction. Further, since we are not sure about the exact plan for this section of the fortress, there would be a large possibility of making irreversible mistakes in the interpretation of several architectural details. Instead, a decision was made to create a lightweight contemporary perforated wooden structure which would provide both an outline of the Main Gate, and the wall that leads from that gate to the little harbor below. Now the Main Gate resonates as a silhouetted slated frame showing in a less permanent and lighter wood construction only the basic features of the Main Gate.

As a result of extensive research examining the fortress in different periods, the decisions about the height and shape of the new gate were made. In order to show the general form of the Bab-ı Kebir, a light wooden structure was proposed which would contrast with the stone walls of the fortress but does not jar, or seem out of place. This language of design, in which wooden elements are used, was also employed for the now missing crenellations on the East Tower and the roof of the Domed Building.

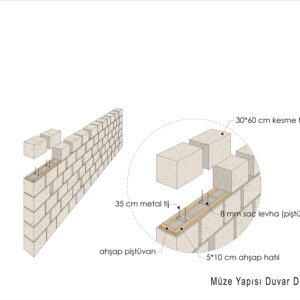

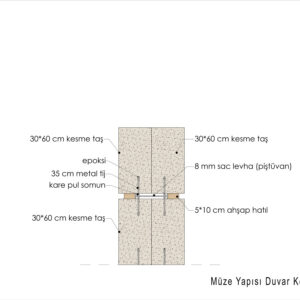

A new building was designed for the museum in order to facilitate access to the fortress and its upper courtyard, to exhibit the archaeological finds from the site in appropriate conditions, and to provide places for service areas such as toilets, an infirmary, and other technical needs which would not damage the fabric of the historical buildings. The walking path in the upper part of the fortress came to light as a result of the excavations and helped to determine the form and the circulation patterns intended for the new building.

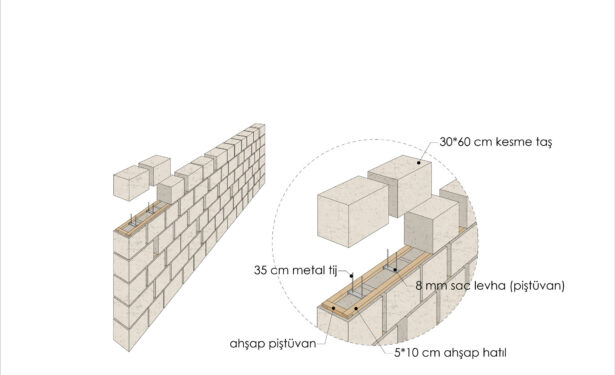

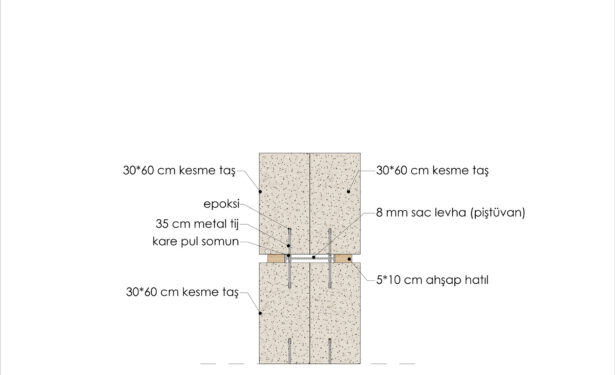

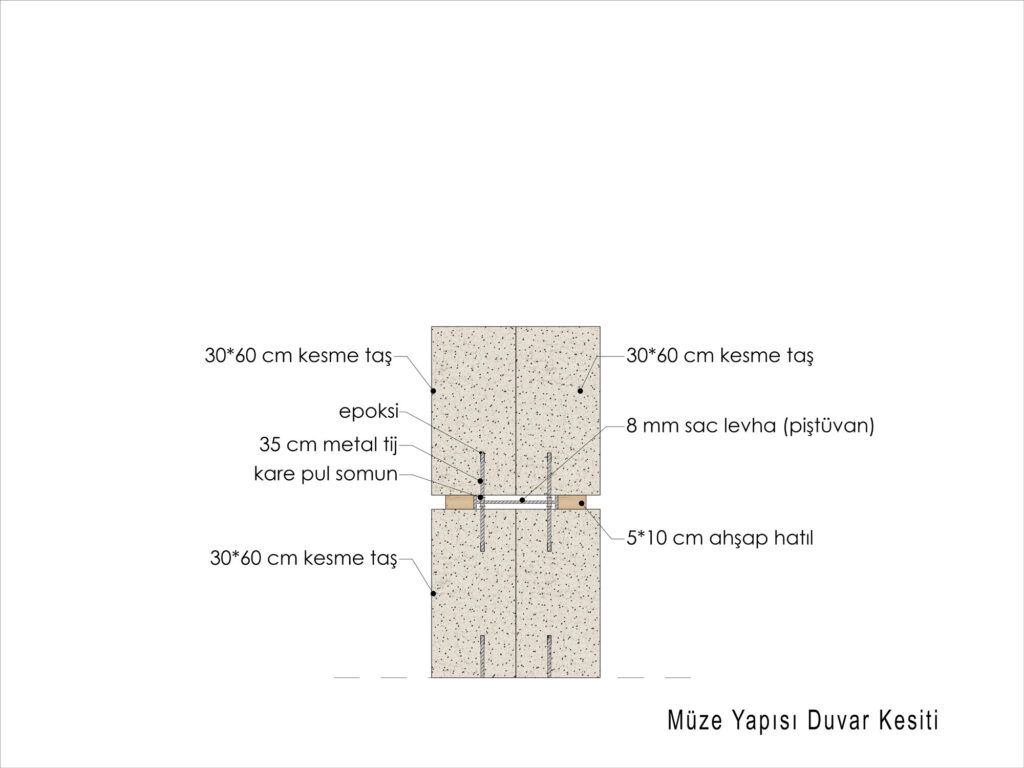

The outer shell of the new building was formed with large blocks of the same type of stone used in the construction of the fortress, and due to the resemblance of material the visible impact of the museum building is reduced. The wooden beam support system used in the original Ottoman walls of the fortress were a source of inspiration for the museum building. The walls of the historical ramp that divides the museum building were preserved, and the traces of the sections that have been lost were marked with Corten steel surfaces.